Evidence-based, Cost-effective Interventions to Suppress the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Rapid Systematic Review

How can we control the COVID-19 pandemic cost-effectively? I worked with Tomas Pueyo’s group around the clock to answer that question. We found that some interventions are way more cost-effective than others (e.g. for H1N1 influenza, contact tracing was estimated to be 4,363 times more cost-effective than school closures—$2,260 vs. $9,860,000 per death prevented [Madhav et al. 2017]).

I first wrote about COVID-19 on March 13. Since then, in response to the pandemic, countries implemented a range of interventions urgently, often without a clear picture of their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. What is the evidence? When we started our search, we found that it looked slim. Indeed, earlier reviews have concluded that the evidence for these interventions is lacking (except for hand washing and face masks). But those reviews included only randomized trials (considered high-quality evidence).

In our systematic review, we included a broad range of study designs to summarize the evidence of all levels of strength and guide urgent decision making. In this context, we believe that evidence of lower quality is better than no evidence at all. Especially if it can help avoid unnecessary damage to the economy and other harms.

For example, a popular intervention is school closures, which currently affect over 1.5 billion (almost 90%) of the world’s students (WHO, 2020). In the US, this has been estimated to cost $10 to $47 billion for 4 weeks (Lempel et al. 2009). Contrast that with contact tracing and case isolation, which as we saw above, has been estimated to be 4,363 times more cost-effective for H1N1 influenza ($2,260 vs. $9,860,000 per death prevented).

We felt we should get the word out as soon as possible, so we submitted our findings in rapid systematic review format in a preprint.

Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions to suppress the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review

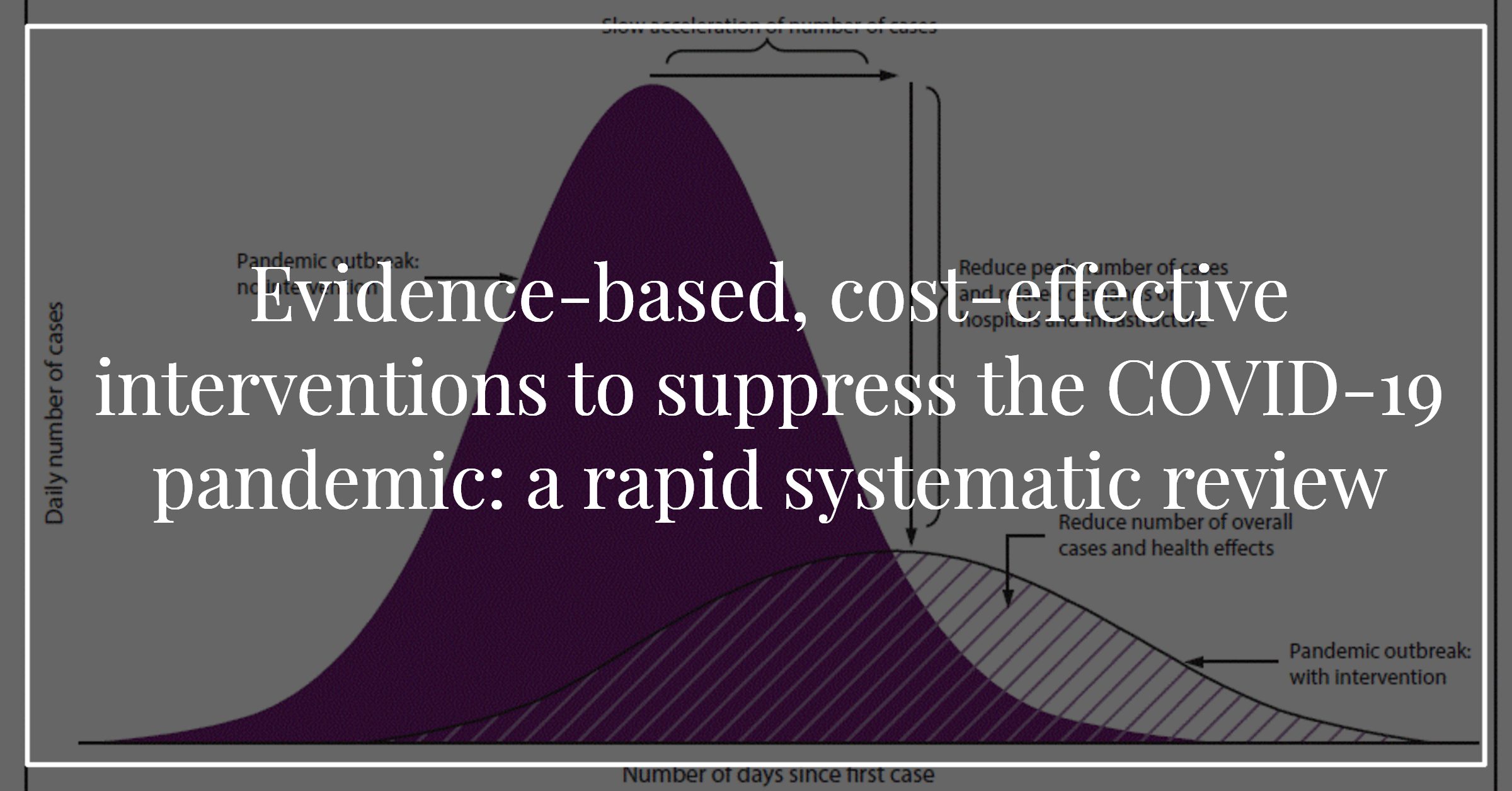

Background: Countries vary in their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some emphasise social distancing, while others focus on other interventions. Evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these interventions is urgently needed to guide public health policy and avoid unnecessary damage to the economy and other harms. We aimed to provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence on epidemic control, with a focus on cost-effectiveness.

Methods: MEDLINE (1946 to March week 3, 2020) and Embase (1974 to March 27, 2020) were searched using a range of terms related to epidemic control. Reviews, randomized trials, observational studies, and modelling studies were included. Articles reporting on the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of at least one intervention were included and grouped into higher-quality (randomized trials) and lower-quality evidence (other study designs).

Results: We found 1,653 papers; 34 were included. Higher-quality evidence was only available to support the effectiveness of hand washing and face masks. For other interventions, only evidence from observational and modelling studies was available. A cautious interpretation of this body of lower-quality evidence suggests that: (1) the most cost-effective interventions are swift contact tracing and case isolation, surveillance networks, protective equipment for healthcare workers, and early vaccination (when available); (2) home quarantines and stockpiling antivirals are less cost-effective; (3) social distancing measures like workplace and school closures are effective but costly, making them the least cost-effective options; (4) combinations are more cost-effective than single interventions; (5) interventions are more cost-effective when adopted early and for severe viruses like SARS-CoV-2. For H1N1 influenza, contact tracing was estimated to be 4,363 times more cost-effective than school closures ($2,260 vs. $9,860,000 per death prevented).

Discussion: A cautious interpretation of this body of evidence suggests that for COVID-19: (1) social distancing is effective but costly, especially when adopted late and (2) adopting as early as possible a combination of interventions that includes hand washing, face masks, swift contact tracing and case isolation, and protective equipment for healthcare workers is likely to be the most cost-effective strategy.

Funding: Louise Potvin holds the Canada Research Chair in Community Approaches and Health Inequalities (CRC 950-232541). This funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

***

The preprint is on medRxiv (founded by Yale University, the British Medical Journal, and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). They screen studies before posting them, but do not peer review. So keep their disclaimer in mind when looking at our review on cost-effective interventions to suppress the COVID-19:

“Preprints are preliminary reports of work that have not been certified by peer review. They should not be relied on to guide clinical practice or health-related behavior and should not be reported in news media as established information.”

Big thanks to my co-authors: Tomas Pueyo, Matt Bell, Genevieve Gee and Louise Potvin.